While the absence of robust trial evidence may indicate that education is ineffective in the prevention of foot ulcers in people with diabetes common sense would suggest the opposite. Indeed, it is possible that educational programmes may appear ineffective when applied in a standard way to large and relatively unselected populations (as required by the conditions of a randomised controlled trial) and yet may be beneficial when delivered more flexibly in order to meet individual needs.

In planning an education programme designed to prevent foot ulcers the authors have sought the views and experiences of people given foot care education, with a particular focus on its content and delivery. NICE guidelines (2004) state: ‘Education is an essential element in the empowerment of people with diabetes, helping an effective partnership between healthcare professional and individual develop, which is key in achieving effective care.’ It was intended that an effective partnership would be established by incorporating patient views into the planned intervention in any future study.

Methods

This study constituted part of the Footbridge Feasibility Study and took place within Gedling PCT in Nottingham, (now incorporated into the newly established Nottinghamshire County Teaching Primary Care Trust), which had a population of just over 96 000 and 15 GP surgeries. The study was approved by one of Nottingham’s two Local Research Ethics Committees as well as by the Department of Research and Development of Nottingham’s PCTs and complied with research governance guidelines.

Participants in the present study were those identified as having loss of peripheral sensation during routine examination in the GP surgery. Peripheral sensation was tested using a 10 g monofilament applied to a site without callus on the dorsum of the hallux, just proximal to the nail bed. The stimulus was repeated four times on both feet in an arrhythmic fashion. Loss of peripheral sensation was defined as failure to perceive five or more stimuli out of a total of eight on both feet combined (Perkins et al, 2001).

Letters were sent to 63 people identified in this way, inviting them to take part in a single semi-structured interview. Those that accepted were sent a letter, information sheet and consent form for completion prior to the interview. Interviews were carried out in the participant’s home with other family members or carers present, conducted by one of two researchers and were later transcribed. Analysis of the transcripts was carried out independently by three researchers using the framework approach (Ritchie and Spencer, 2002). A thematic framework was then devised and the researchers analysed the transcripts according to this framework.

Results

Of the 63 people to whom letters were sent, 39 had never had a foot ulcer and 24 had either a current or previous foot ulcer. Replies were received from 27 individuals: 22 agreed to be interviewed and 5 declined. Three of the 63 had died. Of the 22 who accepted, 18 (12 male and 6 female; mean age 72 years) were available for interview. Ten (six male, four female; mean age 73 years) had not had an ulcer, while eight (six male, two female; mean age 69 years) had either a current or previous foot ulcer.

Three main themes were drawn from the transcript analysis: knowledge, foot care education and current behaviour; and preferences for education. Because of the aim of the study and structure of the questioning, it was the latter that received the greatest emphasis.

Foot ulcer knowledge

Participants were asked if they knew what a foot ulcer was and what one looked like. They were also asked if they knew what caused ulcers and what they would do if they thought they had one.

Most interviewees did not know what a foot ulcer was (one person commented ‘I haven’t a clue’) or what one looked like, and some thought that the term ‘ulcer’ referred only to leg ulcers. Some members of the ulcer group were not aware that they had ever had a foot ulcer, despite it being documented in their clinical notes or even when an ulcer had led to their attending a specialist diabetes foot clinic. None knew the exact cause of foot ulceration, but some referred variously to circulation, neglect, numbness and badly fitting shoes. When asked what they would do if they developed a new ulcer, all reported that they would contact their GP.

Foot care education and current behaviour

People in both groups carried out ‘normal’ foot care behaviour (such as washing feet daily and applying cream), which had not necessarily been taught as part of an education programme in diabetic foot care. Those in the ulcer group tended to report specific diabetic foot care behaviour (for example, checking feet daily, checking shoes), which was more likely to have been taught.

Of those who remembered being given foot care advice, the majority said that it had taken place when they were diagnosed with diabetes, and that it had come from a variety of healthcare professionals: podiatrists, practice nurses, district nurses, hospital staff, GPs; and from Balance magazine. The type of education had varied from leaflets to one-to-one advice to group sessions. A number of people from both groups had received advice regarding footwear and all said that it had been given by the podiatry department.

Participants were asked about the issues surrounding whether or not they followed foot care advice. Some mentioned a degree of self blame for not following advice, but also said they felt that ‘it’ll never happen to me’.

“Complacency sets in, yes. Diabetes is, if I break my arm, you can see that, put it in plaster and watch out but you can’t see diabetes. So a broken arm, leg, you can see these things. But if it’s in your blood, you can’t see, feel or do anything. You have a tendency not to care about it so much, because it isn’t actually a pain in the leg, it’s not actually a toothache or an earache.”

Preferences for the delivery of foot care education

Participants were asked about their preferences for education, including when and where it should be provided and by whom. They were also asked their views on the best way in which educational information should be delivered.

Who should be giving foot care education?

Those who had not had an ulcer previously gave a variety of answers. These ranged from receiving education from several health professionals to, more simply, ‘somebody who knows what they’re on about’. They also included ‘myself’ (the patient) and ‘companies that sell the products’. One participant was uncertain and having originally suggested the doctor, changed her mind later and said the chiropodist (podiatrist).

The general consensus in the ulcer group was that advice on foot care should come from the GP or whoever made the original diagnosis of diabetes. One person felt this because they were familiar with their GP and would not have been comfortable with anyone else. One of the respondents had recently had a positive experience with a podiatrist and therefore said that she would have liked the information to come from the specialist. One of the participant’s wives said that the diabetic clinic should be responsible for providing foot care information and advice. One participant suggested that Diabetes UK should provide a starter pack for all newly diagnosed cases.

How would you like education to be given?

General attitudes to education in both groups included some very personal views, with others giving what they thought would be best for all rather than just what they themselves would like. However, those with a history of ulceration generally had more ideas on how information should be provided to others. One said that any information at all would be helpful, while another suggested that education should be given in two stages: general education followed by special sessions on all aspects of diabetes care including one with an emphasis on feet. Another participant felt that it was important to provide the correct level of information to ensure that the message given was positive to avoid inducing fear. This participant also suggested that a more ‘systematic programme of awareness raising’ would be beneficial, but then pointed out that even though he was suggesting this, he may not himself attend if such a programme became available. Other members of this group acknowledged that although they were aware of the importance of education, they may not themselves have been responsive to it before they had had any problems with their feet.

Educational media

Those interviewed had very different ideas of how education should be provided. All agreed that leaflets or booklets would be helpful as they could take them home, read them at their leisure and refer to them as necessary, to check if their actions are correct, and some suggested that a list of Do’s and Don’ts would be useful. One person from the ulcer group stressed the importance of keeping the material concise and to the point and added that such leaflets should be widely available.

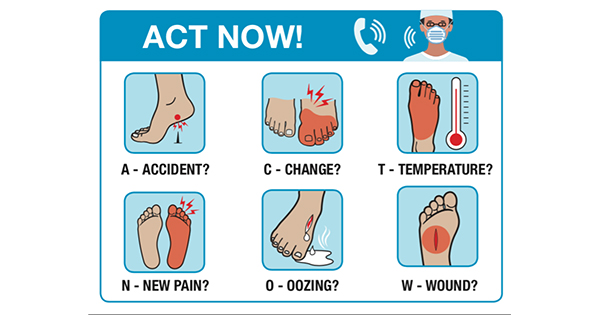

Participants were asked about the usefulness of pictures or diagrams. The majority of people in both groups thought that pictures would be helpful in explaining foot problems. Some in the ulcer group suggested it would be useful to know what to look out for and to illustrate examples of foot problems, although not all felt that this was necessary. Some participants were concerned that pictures may scare people, but one went on to say that despite this he thought they were necessary. Another said that it may put some people off, but it was necessary for people with diabetes to know what may happen.

“I greatly believe that it has to be graphic, people have to see what can happen to their feet if they don’t take precautions.”

“I don’t know, because you could scare people an awful lot… I’ve seen pictures [of an ulcerated foot] it’s horrifying, but I think it’s necessary…”

The idea of using videos or DVDs received mixed feedback, with some saying they would prefer audio tapes to talking to a healthcare professional, while others either did not have a video/DVD player or said that they had never used one. There was no difference in answers from those who had previously had ulcers and those who had not.

Most involved reported that they did not have either a computer or the skills necessary for Internet or computer-based learning. One person commented that the ‘younger generation’ may prefer it.

Format of person-to-person education

People were asked if they would like to attend group sessions to receive education, or would prefer verbal education to be delivered one-to-one. Both groups gave different and individual answers, indicating that the preferred method of education delivery varies. Some people from both groups thought that group education with practical demonstrations would be a good idea. However, most said that they would not want group sessions and would prefer one-to-one education.

Timing of education

Most felt that information should be provided at the time of diagnosis of diabetes, or at their first podiatry appointment, although one person was also worried about the high volume of information that they received at that time.

Factors which might limit access to education

Participants from both groups mentioned a number of factors which might prevent them from attending any form of special education session. These included work commitments and looking after preschool children (as parents or grandparents). It was suggested that sessions should be provided locally or at home to enable those with mobility problems or financial constraints to attend. One person felt that the whole family should be provided with information, not just the person with diabetes. These factors were important in influencing people’s preference for the place where education might take place, as was a general dislike of hospitals.

“I don’t like going to hospitals, it’s a dear job if you go regularly.”

“Come to me duck, because I only walk a bit duck.”

“Sometimes I get a bit on edge if I go to the hospital, with waiting and that, you know.”

Discussion

There was a general lack of knowledge about diabetic foot care among the people interviewed, and there was little obvious difference between those with a history of foot ulceration and those without. All reported that they had been given some information, but there was no uniformity in the type and extent of information that had been provided. Advice had not been given on a regular basis and had not been systematically reinforced. Knowledge of the causes and appearance of foot ulcers was poor. Many people did not know what a foot ulcer was – even when they had had one. Participants had widely differing views about the way education should be provided and what was most suitable for them. The majority felt, however, that leaflets about foot care and pictures or diagrams would be useful and most felt that one-to-one sessions would be preferable to group education. Some would have welcomed the use of videos but none expressed any interest in computer-based learning.

Apart from the surprising finding (previously noted by Garrow et al, 2004), that some people do not understand what is meant by the term ‘foot ulcer’, the principal findings from the study were as follows:

- There was a wide variation between stated views and preferences.

- Written materials such as leaflets were supported by many of those interviewed.

- The use of visual images in foot education was considered important by some.

- In general there appeared to be a degree of reluctance to consider group education.

- People did not feel that education should be centred in hospitals.

Future attempts to substantiate the benefit of education in this field should take these findings into account.

In addition, the findings should be noted by those who plan the implementation of programmes of foot care education even in the absence of clear evidence of their effectiveness. Others, however, would argue that in the absence of clear evidence of effectiveness, it would be a mistake to divert inappropriate proportions of scarce resources (money and professional time) into formal education programmes and away from clinical care.

Conclusion

While the need for education is emphasised, there is no clear consensus as to what foot care education people with diabetes should receive, when they should receive it, how and from whom. Individuals with neuropathy had differing ideas on how education might be best provided for them, but most wanted one-to-one verbal information, supplemented by good quality leaflets with illustrations. Very few expressed interest in audiotapes, videos, DVDs, or any form of computer-based learning.