Readers are directed to the PDF version of this article, where additional information can be viewed.

Until 5 years ago, as a GP I generally offered my patients the usual “eat less and move more” approach to dietary advice, without seeing much benefit. When my husband, the television presenter Michael Mosley, discovered that he had type 2 diabetes, I joined him in trawling the research to find ways of reversing his diabetes through diet. In the process, Michael developed the 5:2 Diet, lost 10 kg and succeeded in reversing his hyperglycaemia without the need for medication. Whilst refining the diet, he came across Prof Roy Taylor’s research on the use of very-low-calorie diets (VLCDs) to reverse diabetes, following which he developed the 8-Week Blood Sugar Diet (BSD).

Impressed by research demonstrating the potential benefits of low-calorie, low-carbohydrate Mediterranean-style diets on weight loss, reducing blood glucose and improving diabetes, I have now spent several years working with patients to help them implement this diet.

The Mediterranean diet

The traditional advice for people with diabetes was to eat less fat and increase carbohydrate consumption. Yet this advice does not slow, let alone reverse, the progress of type 2 diabetes. Indeed, there is good evidence that it is the increasing intake of refined carbohydrates, along with decreasing intake of fibre, that is driving the rising prevalence of type 2 diabetes (Gross et al, 2004). In randomised controlled trials, low-fat diets have often performed poorly when compared to alternatives.

The Look AHEAD Trial randomised 5145 overweight or obese adults with type 2 diabetes to an intervention group or control group (The Look AHEAD Research Group et al, 2013). The intervention aimed at reduced caloric intake, with <30% of calories from fat, and increased physical exercise. The control group received diabetes support and education. After 10 years, the trial was halted for “futility”, as there were no measurable differences in rates of heart disease or stroke between the intervention and control groups, although there was significant weight loss.

The two-year DIRECT (Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial) study, during which 322 moderately obese subjects were randomised to a low-fat, Mediterranean or a low-carbohydrate diet, found the low-fat diet least effective for weight loss (Shai et al, 2008). After 2 years, the low-fat group had lost an average of 2.9 kg versus 4.4 kg for the Mediterranean-diet group and 4.7 kg for the low-carbohydrate group. The biggest improvements in fasting glucose levels were in the Mediterranean diet group.

Furthermore, a systematic review of dietary approaches to the management of type 2 diabetes looking at randomised controlled trials lasting over 6 months, found that low-carbohydrate, low-glycaemic index and Mediterranean diets all led to a greater improvement in glycaemic control when compared with controls that included low-fat diets (Ajala et al, 2013). The low-carbohydrate and Mediterranean diets also led to significantly greater weight loss compared to their controls.

Consequently, I recommend that my patients adopt a low-carbohydrate Mediterranean-style diet. This involves:

- Reducing refined, simple and starchy carbohydrates (including pasta, bread, white rice and starchy vegetables, such as potatoes) and breakfast cereals (other than coarse porridge).

- Avoiding fruit juices, sweet drinks and smoothies.

- Reducing fruit intake to 1–2 portions per day (preferably hard fruits or berries).

- Moderately increasing intake of healthy fats (including more olive oil, rapeseed oil, nuts, avocado, eggs and some full-fat dairy products), whilst avoiding trans and processed fats.

- Including plenty of vegetables, oily fish and occasional meat.

This approach can be applied to most diets around the world, from Scandinavian to Asian.

The benefits of the Mediterranean diet are supported by the findings of a systematic review of meta-analyses and randomised controlled trials (Esposito et al, 2015), including the PREDIMED trial.

PREDIMED randomly allocated 7400 people in Spain (aged 55 to 80 years) at high cardiovascular risk to either a standard low-fat diet (lean meat, low-fat dairy, cautious use of oil and plenty of starchy food, such as potatoes, pasta and rice) or one of two Mediterranean diets (rich in oily fish, nuts, olive oil, eggs, pulses and whole grains, as well as dark chocolate and a glass of red wine with their meal). Each group was encouraged to eat plenty of fruit and vegetables. Over a mean follow-up period of 4.8 years, those on the Mediterranean diets put on less weight around their waists, were 30% less likely to die from a stroke or heart attack and were half as likely to develop diabetes compared to the low dietary fat group (Estruch et al, 2013).

In addition, a systematic review by Ajala et al (2013) concluded that “low-carbohydrate, low-glycaemic-index, Mediterranean, and high-protein diets are effective in improving various markers of cardiovascular risk in people with diabetes”.

Can type 2 diabetes be reversed?

In healthy individuals, insulin helps to remove glucose from the circulation. Poor diet, lack of exercise and a build-up of abdominal fat can lead to the development of insulin resistance. As a result, the pancreas needs to produce ever-higher levels of insulin in an attempt to reduce blood glucose levels, a condition known as hyperinsulinaemia). Individuals may feel constantly hungry because their cells are feeling “starved”, yet are less able to make use of the circulating glucose and fatty acids. Eventually, diabetes develops.

Steven and Taylor (2015) demonstrated that this process can be reversed by weight loss. In this pilot study, 29 people with type 2 diabetes completed an 8-week VLCD. Overall, 87% of participants with short-duration diabetes (<4 years) and 50% of those with long-duration diabetes (>8 years) achieved non-diabetic fasting plasma glucose levels and had stopped all antidiabetes medication by week 8.

The much larger multicentred DiRECT cluster-randomised controlled trial allocated 149 overweight or obese adults with type 2 diabetes (duration <6 years) from primary care to a low-calorie diet (just over 800 kcal/day). Almost half achieved remission to a non-diabetic state and remained off antidiabetes drugs at 12 months, compared to 4% in the control (best-practice care) group. Two-year data are awaited. The investigators concluded that remission of type 2 diabetes is a practical target for primary care (Lean et al, 2018).

It is, of course, likely that individuals who regain weight will find that their glucose levels return to the diabetes range.

Examples in general practice

A small trial in general practice by GP Dr David Unwin of a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet has been conducted (Unwin and Unwin, 2014). Nineteen people with type 2 diabetes or pre-diabetes were given advice on a low-carbohydrate diet by a GP or practice nurse, as well as either 10-minute one-to-one progress reviews or evening group meetings every month. After 7 months, only one participant had dropped out of the study. The rest all had significant weight loss (mean=8.6 kg). Average HbA1c reduced from 51 to 40 mmol/mol (6.8% to 5.8%). Despite the higher fat intake, the mean cholesterol level dropped and liver function improved for nearly all participants. Subsequently, the practice, of 9000 patients, reported savings of around £45 000 on the diabetes-related drug budget. In 2016, the practice continued to report savings, spending £37 000 less in 2016 than was average for the CCG on drugs for diabetes alone, excluding insulin.

From 2013 to November 2017, 118 of Dr Unwin’s patients with type 2 diabetes were counselled in the practice about the low-carbohydrate diet, of whom 91 have taken it up. The average improvement in HbA1c for that cohort was 20.4 mmol/mol (1.9%), with an average duration on the diet of 21 months and a weight loss of 8.76 kg.

One of my early adopters demonstrated a typical response to the BSD for an overweight person newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. His initial HbA1c was 58 mmol/mol (7.5%). Almost 3 years later, his HbA1c is 39 mmol/mol (5.7%) off medication, so he is in remission. He looks and feels well, and his blood pressure and lipids have also improved.

Impact of the BSD in general practice

To begin to assess the impact of the BSD on HbA1c, a limited study was conducted in my general practice surgery at the Burnham Health Centre. Between the end of 2015 and mid 2016, a series of 24 consecutive patients, who were following the BSD approach, was observed in routine surgeries.

These individuals had been recently diagnosed with diabetes or pre-diabetes, or had poor glycaemic control and were considering additional medication or starting insulin therapy. After consultation, they agreed to adopt the BSD approach.

Initial results indicate a positive effect on HbA1c. Of the 24 individuals, 23 showed improved readings and one an increase. The average HbA1c reduction across all participants was 18 mmol/mol (1.6%), with a median change of 12 mmol/mol (1.1%).

Furthermore, most of the participants reduced their medication or avoided starting it. Some even stopped taking medication as a result of improvements in their hyperglycaemia.

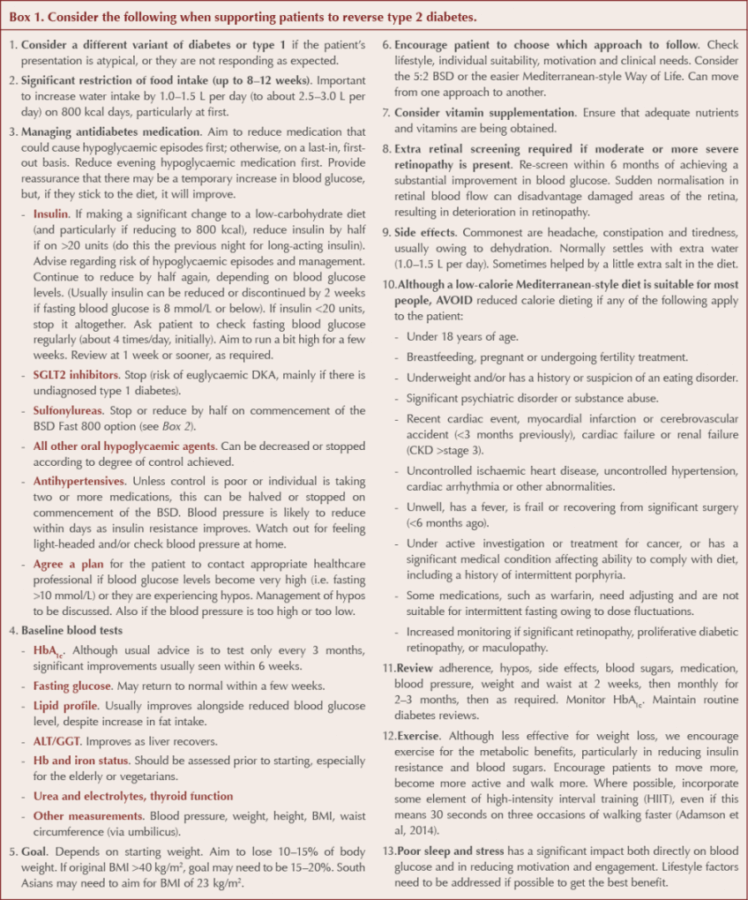

While this data is very limited and requires a great deal more analysis, I am hugely encouraged by the findings and believe that this low-carbohydrate approach can benefit suitably motivated individuals when implemented in the primary care setting. It is, however, essential that patients are helped and supervised when switching to such a diet. Advice on what to consider when providing such support is shown in Box 1.

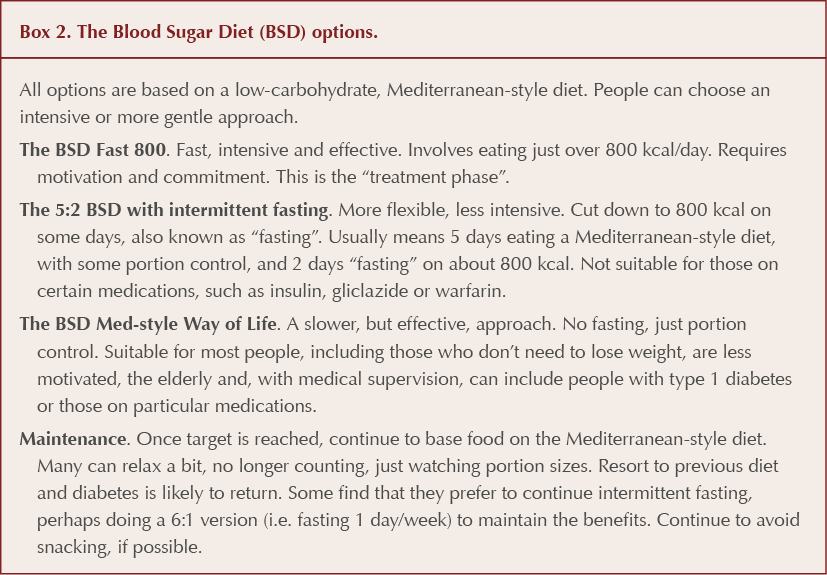

The 8-Week Blood Sugar Diet Recipe Book

The Blood Sugar Diet Recipe Book is a practical companion to Michael Mosley’s original book, The Blood Sugar Diet (which looks at the evidence on weight loss and diabetes, provides a detailed plan and some recipes). The recipe book includes the plan outlined in Box 2 as well as lots of simple daily recipes for a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean-style way of eating on around 800 kcal/day. There are also practical suggestions for swaps to reduce sugar and starchy carbohydrates, and a 1-month, 800-kcal menu plan.

The mortality benefits of smoking cessation may be greater and accrue more rapidly than previously understood.

2 Apr 2024